Autumn’s Country

On the eve of Wang Jun’s departure, her brother Fai entered her room, and found her before her mirror.

“I look such a fright,” Jun said. Her face, devoid of makeup, was wan, almost colourless. Under her eyes were dark circles, like bruises. Fai knew that for the past seven days she had stayed up late, packing clothes and jewels for the journey to her bridegroom’s house, and the wedding that awaited her there.

“Nonsense,” he said. His hand trailed on her shoulder, settled at the nape of her neck. “You’re lovely.”

Jun made a face. “You’d say that.” She stared at her pale hands, and back at the mirror. “Do you think Zheng Yi will like me?”

“Of course,” Fai said. “Zheng Yi’s no fool; he knows what he’s getting. You’d make any man a fine wife.” He paused, asked, softly, “You are happy, aren’t you?”

“Of course,” Jun said, startled. “Why shouldn’t I be?”

“Ming-Mei was happy,” Fai said, hating himself for reminding Jun of the dead on this day, of all days. Ming-Mei, their older sister, had been happy. She had laughed as she packed her things for the journey to her groom’s house, and embraced Fai with a smile, telling him to behave himself now that she was out of the house. No one, least of all Fai, had seen the fear in her eyes, or whatever had driven her to leap from her horse into the waters of the Yang Tse river under the horrified gaze of her escort.

Jun did not answer for a while, staring at her image in the mirror. “Yes,” she said. “She did sound happy.” Her hands tightened on the table wood. “You’re just trying to frighten me. I wouldn’t ever act like her.”

“I hope not,” Fai said. He shouldn’t have brought Ming-Mei up. But if he had asked Mei the same question on the eve of her departure, perhaps she would have given him a true answer. And perhaps she’d still be alive.

“I miss her,” Jun said. “How we used to tease each other, and the races we’d have in the courtyard. I thought that grief would pass, in time. But it still hurts the same.”

“I know,” Fai said, gently. “Seven years is nothing. I don’t think it’s a bad thing for us to mourn. She’ll see that from her place among our ancestors, and be happy we remember her.”

“Maybe,” Jun said, her face unreadable. “I’m not her, Fai. I want this wedding. I’ve waited so long for it. I’ll have a household of my own, and Zheng Yi’s love, and we’ll have many children together, and they’ll play together on the grass–” Her eyes had taken on a dreamy glaze.

Fai waited for her voice to trail off before he said, “I’m sorry I talked of Ming-Mei. Nothing is going to happen to you. You’ll have all that you dream of, and more. I promise.” He said, inexplicably embarrassed, “I only want you to be happy.”

She turned to him, her dark eyes filled with joy. “Thank you, brother. You have no idea how much this means to me.” Her gaze went back to the mirror, and she started undoing the bun in her hair, preparing herself for sleep.

Fai left her then. In the courtyard of the house, horses neighed, impatient for the journey ahead, the journey that would bring Jun to her groom’s house, Jun with her wedding clothes packed in the saddlebags, smiling all the way.

Had Fai known what would happen later, he would never have left her alone.

***

In the morning, the household woke and servants started banking the fires in the kitchen. Jun’s escort assembled in the courtyard, ready for the long journey, and Fai’s mother and father started fussing on the things Jun would take with her–yet one more time. But Jun herself did not come down.

It was Fai who worried first, Fai who searched around the house, and, not finding her, finally climbed the stairs to her room. He knocked, and only silence answered him. He knocked a second time and, when no answer came, he cautiously slid open the door and entered the room.

The braziers were cold; her hairpins still lay on the table before the mirror. The bed looked slept in, yet Jun herself was nowhere to be found.

Fai, a hollow feeling growing in his stomach, called for her, knowing there would be no answer.

Only one thing looked out of place: on the table, next to the hairpins, was a poem on rice paper, crumpled violently as if it hadn’t pleased. It wasn’t Jun’s handwriting.

It read,

“My house is hidden behind wisteria-covered walls

Waiting for you

The door is strong and unbreached

We will be happy together

I have hung red lanterns in your quarters

And the moon shines through the shutters of cedar

I am waiting for you.”

It wasn’t signed. Fai picked it up, staring at the characters until they all blurred before his eyes. He saw, again and again, Jun arranging her hair before the mirror, Jun smiling playfully at him.

Jun.

***

Fai’s first thought was to check the horses, but none of them were missing. The four men of Jun’s escort milled aimlessly in the courtyard; he told them, curtly, to go back to their quarters.

“But–” the captain said.

“There’s no need for you,” Fai said. “Not any more.” He kept his voice even, trying to show none of his worry.

They dispersed, refusing to look him in the eye. He knew what they thought. They had failed in their duty. But he, who was Jun’s brother, had been the one to truly fail. He remembered the promise he had made her on the previous evening: that nothing would happen to her. What a fool he had been.

His parents looked away when he showed them the poem, almost as if embarrassed.

“Did you know about this?” Fai asked, keeping his voice toneless–he wouldn’t accuse them, they looked as distressed as he was.

“Yes,” his mother said. Her eyes wouldn’t meet his.

“Tell me.”

“It’s of no consequence.”

“Of no consequence? My sister is gone, Mother. Your daughter has disappeared, and you want me to accept this. What should I do? Mourn her and forget, as we did for Ming-Mei?”

His father’s eyes blazed. “Respect, Fai. Have we taught you nothing?”

“I’m sorry,” Fai said. He held the paper out again. “Please. Tell me. Maybe we know where she’s gone.”

His mother sighed. “We’ve read those words before, Fai. They were part of what Ming-Mei’s groom sent her a few days before her wedding.”

“Ming-Mei’s dead.”

“We haven’t forgotten.” His mother’s voice shook, a little, and her eyes shone in the sunlight. “And Mei’s groom hasn’t either, I think.”

“What does he have to do with this?”

His parents exchanged glances. At last Fai’s father said, “Si-Jian Li was a sorcerer, a practitioner of the black arts. We didn’t know–we didn’t find out until after Ming-Mei had died. He sent a mynah bird to us, with a message. He said that since her death had cheated him of his wedding, we owed him another bride.”

“Jun?” Fai’s heart sank. “And you never told me.”

“You were too young,” his father said. “And it was none of your concern.”

“She’s my sister. I had a right to know.”

“Let’s not argue over that,” his mother said, gently. She went on, “We paid a Taoist monk at the temple for a spell of protection for Jun. One that would last for twenty years.”

“And it didn’t last.”

“No,” his father said. “We are not fools. We had guards around the house, ever since Jun became engaged to Zheng Yi. And we doubled them last week. We feared Si-Jian Li would come for her and force her to marry him.”

“And he did come.” Fai stared at the poem again, remembering Ming-Mei riding out of the house with her escort, remembering her smile. “Fengjin,” he said. “That’s where that sorcerer lived, isn’t it?”

His mother nodded.

“Then I’m going,” Fai said.

“You can’t. He’ll kill you.”

“I’m not leaving him to destroy another one of my sisters,” Fai said, grimly. “All Jun wanted was to find a kind husband. She doesn’t deserve this.”

“Fai–” his father said.

“You’re not going to stop me,” Fai said.

“We are your parents.”

“Yes,” Fai said. “But I have a sister to think of. I’ll bring her back, no matter the cost. I’ll bring her back alive, and see her safely wedded.”

“Fai–” his father called, but Fai had already turned, and left the room.

***

Fai took a horse from the stables–not the bay mare that should have carried Jun, but the grey gelding that was his favourite.

Before leaving, he wrapped a jade disk pendant around his neck–the symbol for the harmony of Heaven and Earth, a pitiful defence against the black arts, but the only one he had. From the armoury he took a sword, with the hilt in the shape of a dragon, for he would not be weaponless even in the face of magic.

In the courtyard he gathered the four members of Jun’s escort, and asked them if they would go with him.

“Why do you ask?” the captain said. “We swore to protect her.”

“We go against a sorcerer,” Fai said. “Steel won’t avail you.”

The captain shrugged, and put his hand on the hilt of his sword. “Sorcerers die like any other man,” he said. “We’ll come.”

Fai nodded, although he suspected five men would not make any difference against Si-Jian Li. Still, every hour that passed meant Jun got further and further away from him. That, perhaps, she was getting forced into a wedding she had no wish for. He could not afford to dally.

They left the house under low, grey clouds that threatened to split open at any moment, drenching them with the rain they held. Fai was in the lead, and the four others followed in a tight group. They made good time: they were armed, and looked dangerous enough to discourage bandits. They stopped at inns only to rest their mounts, and sleep without dreams. Fai asked every innkeeper whether they had seen Jun, but when they gave him only a blank stare, he knew they had not.

One evening, they reached the banks of the Yang-Tse; the inn they would stop at lay a little to the left in the shadow of the hills, promising warmth and shelter. But there was one thing to be done first; respects to be paid.

Fai dismounted under the watchful gaze of his escort. By the light of the full moon overhead, he cast a few orchid flowers in the current, in memory of Ming-Mei.

“I’m sorry,” he said, aloud. “I failed you. Please do not let me fail Jun as well. Let her have the wedding she wanted.” The roar of the river drowned his words–he could not be sure that the spirit of Ming-Mei would even hear them.

They reached Feingjin a few days later, and went straight to the house of Si-Jian Li–Ming-Mei had talked enough of where it was for Fai to have those words engraved in his mind.

It stood a little away from the village, on a northward road. Its walls were high, covered with wisteria, as in the poem. He could not even see the house. Fai eyed the walls, and decided he wouldn’t be able to climb them. He wheeled his horse around, and went to the main gate.

It was closed. Silence hung around him as he dismounted and knocked on the lacquered panels. His knock echoed as if in an empty room, but nobody answered.

“That sorcerer keeps a merry company,” the captain said, with a raised eyebrow, as the last echo faded into silence. “Perhaps we can try to scale the walls–”

Fai’s eyes focused on the gate itself.

The paint was old, shot through with cracks. The beautiful images of phoenixes and dragons sporting amongst clouds had nearly faded, and when he withdrew his hand from the panels, scabbed paint came with it. He turned around, studied the walls, and the way the wisteria grew wild, untended to.

It might have been that Si-Jian had fallen on hard times, but Fai had doubts about that. The outside of the house looked more as if it had been abandoned for a long time.

“He’s gone,” Fai said. “Let’s see if we can learn where.”

In Fengjin, he entered the first wineshop he saw, accompanied by the captain–he left the other three men in the street, watching the horses.

“I’m looking for Si-Jian Li,” he said to the shopkeeper.

Silence spread around the room, fell over all the drinkers at their tables. Fai felt like a deformed beggar who had just entered a rich man’s house.

The shopkeeper said, at last, “You should have come a couple of years ago if you really wanted to see him.” His tone of voice implied it was a bad idea. “He died eighteen moons ago.”

“He’s dead?” Fai remembered the poem in Jun’s room. It was nothing, then. It was probably Jun who had found it in Ming-Mei’s things and carried it to her room after he had left. She’d probably liked it for some reason, and wanted to bring something of Ming-Mei’s with her.

Nothing. He’d come all this way on a false trail.

“You’re sure,” he said, half-hoping for a different answer. Beside him, the captain was silent, his face thoughtful.

“Oh yes,” the shopkeeper said. “We all saw the body when the monks brought it back to the temple.”

“What did he die of?” the captain asked.

“Hard to be sure,” the shopkeeper said, and looked away. Fai questioned him further, but no matter how hard he or the captain pressed, no answer came.

Fai went out of the wineshop. The three soldiers were waiting for him. He told them to join their captain inside, and he made his way alone to the Taoist temple.

It stood at the Western Gates, its bulk dwarfing the smaller houses around it. Its gates bore images of Taoist divinities, from the Queen Mother of the West in her celestial chariot drawn by cranes, to Li Tieguai, oldest of the Eight Immortals, leaning on his iron crutch, and carrying the gourd in which he hid his soul.

Fai did not have to wait for long after he had knocked on the gates: a monk opened them and asked what Fai had come here for.

“You were the ones who brought Si-Jian Li back, one year ago,” Fai said. “What did he die of?”

“Si-Jian Li?”

“The man in the wisteria house,” Fai said, curbing his impatience. He sensed a mystery there, in what no one would tell him. A mystery that would tell him where Jun had disappeared. “North of Fengjin.”

“I know who you mean,” the monk said, after a pause, “but I hadn’t yet entered the order at that time. It was Brother Yuan who found him. Come in. I’ll take you to him,” he said, and guided Fai through the corridors decorated with images of the Immortals, to a smaller shrine in a courtyard.

A very old monk was praying before a group of nine painted statues. Eight of them were the Eight Immortals of the Taoist tradition, easily recognisable by their attributes. The ninth, smaller statue didn’t belong there.

Fai stopped, stared at it. It was a woman with hair the colour of rainclouds, and robes of fallen leaves. She rode a chestnut horse over the swirling waters of a river, and ghosts followed in her wake.

But it wasn’t that which stopped him. It was the face, a face he hadn’t forgotten in seven years.

Ming-Mei.

But Ming-Mei was dead. “Who is this?” he asked.

It was the old monk–Brother Yuan–who answered. “That’s Autumn,” he said. “She gathers the souls of drowned men.”

Autumn. “That’s a new statue,” Fai said, still trying to make sense of what he saw.

“I had it made for our temple. I drew the pictures for the sculptor. I’ve seen her,” Brother Yuan said, proudly. “Riding every full moon through Fengjin with the ghosts in her wake. You never forget her once you’ve seen her.”

“I know her,” Fai said, chilled. “I’ve never forgotten her. And her name isn’t Autumn.”

“How would you know her name?”

“That’s my sister. She drowned in the Yang-Tse seven years ago.”

“Your sister?” Brother Yuan asked. His rheumy eyes focused on Fai, and the understanding that filled them was almost as frightening as knowing Ming-Mei might not be dead. “I’m sorry,” Brother Yuan said at last.

“My sister is dead,” Fai said. “She’s not–she’s not an Immortal. She’s not worshipped.”

“The dead do not rise again,” Brother Yuan said, slowly. “They turn into ghosts. They drift into the lands beyond life, their destination determined by the manner of their death. But sometimes, the will to linger is stronger than death itself. Sometimes the dead’s desires transform them.”

“Into this?” Fai said, his hands touching the cold, emotionless statue.

“You knew your sister better than I,” Brother Yuan said. “I don’t have an answer to that.”

Fai thought of Ming-Mei, of Si-Jian’s poem, and of the other things he might have sent her with that final gift. Letters, perhaps. Words that had made her guess that her bridegroom was not a man who would be gentle to her. Ming-Mei had drowned herself rather than marry Si-Jian Li. How much hatred towards her bridegroom had she taken with her into the waters of the Yang-Tse?

Fai said, slowly, as if probing at an open wound, “Si-Jian Li drowned, didn’t he?”

Brother Yuan nodded. “He fell into the river one evening.”

No, not fell, Fai thought, chilled. He’d been pushed. And Jun…

“I need to see Autumn,” he said.

“Why?”

“She has–someone I want.” Jun. Jun who was getting married to a man she didn’t know, as Ming-Mei had done.

“It’s a full moon tonight,” Brother Yuan said at last, looking from Fai to the statue, puzzled. “But Autumn doesn’t relinquish her ghosts.”

“The one I’m looking for is not a ghost yet,” Fai said, inwardly praying to the Eight Immortals that this were true. He had a promise to keep. He’d see Jun alive, and safely married to Zheng Yi.

***

Fai sent the guards to the inn, to get some rooms for the night–there was no longer any point in taking them. Against a sorcerer they might have been of some use; against an Immortal, they would make no difference whatsoever. He did not tell them that; he only dismissed them with a flat voice, dissuading any protest they might have made. He watched them leave in a cloud of dust and then turned back to Fengjin, and the end of his journey.

He sat waiting where Brother Yuan showed him, at the edge of the river that crossed Fengjin–a tributary of the Yang Tse where Ming-Mei had drowned.

He had his sword on his knees, knowing it to be useless against an Immortal. As the chill of the night worked itself in his bones, he watched the stars overhead, thinking of his sisters. Ming-Mei. Autumn.

Jun.

The moon rose over the river, white and bloated. It cast a pale light that gave harsh edges to the branches over him, a pale light that remodelled the landscape into something alien, and Fai shivered.

He heard the hoofs first, the splashing sound they made as they struck the water. Then came the white light, stronger than that of the moon. He rose, shaking, to meet Autumn.

Her hair was the colour of rain-clouds, her eyes as red as fallen maple leaves. She rode her chestnut horse, unheeding of the myriad of ghosts–mostly children–who clustered in her wake, leeched of colours by Autumn’s light. Jun was not among them.

“Ming-Mei,” Fai called.

She stopped her horse, stared at him. She was and wasn’t the sister he remembered. Her face was emotionless, her eyes emptied of everything but a cold anger. “Brother,” she said. “You have no place here.”

“I’ve come for Jun,” Fai said. “Where is she?”

“Safe,” Autumn said. “In my country.”

“Her bridegroom is waiting for her. She has no place there,” Fai said, staring at the pale, expressionless faces of the ghosts.

Autumn laughed. “Has she a place in your world, brother? Should she be handed to a husband like cattle changing hands?”

Fai stood, motionless. “No,” he said. “But she wanted this wedding. Our parents, too.”

“It makes no difference,” Autumn said.

“Their intentions were the best.”

“As when they betrothed me to Si-Jian?” Autumn asked, angrily shaking her head. “A man who would imprison me behind the walls of his house and let me see nothing of the world? You have read the poem.”

“Not that way.”

“You are a man,” Autumn said, contemptuously. “You see nothing.”

“You’re wrong,” Fai said. “I wanted you to be happy. Both of you.” And words he had never spoken worked their way through his mouth; he uttered them, shaking inwardly. “I should have asked you,” he said. “Before you left for Fengjin, I should have asked you. I’m sorry. I should have seen.”

“But you didn’t,” Autumn said.

“No,” Fai said. “There is nothing that will make up for that. But that doesn’t give you the right to take Jun.”

“In my country,” Autumn said, softly, “she has a garden, and a house to herself. She plays the zither when she wants to, and we race each other around the courtyard, as we did when we were children. She is no man’s toy.”

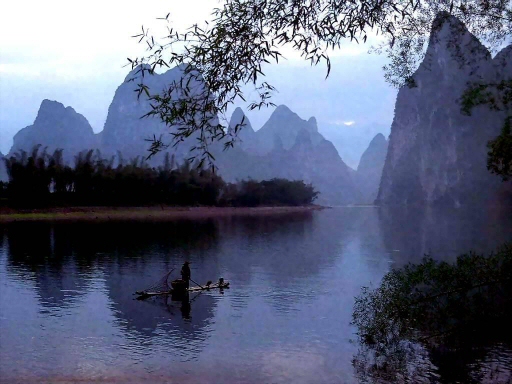

And as she spoke a path opened before her, a gate that revealed a country of hills and rivers, with willow trees and the promise of endless afternoons of golden light, and houses dotted across the hillsides. Birds sang, and children ran forever on the verdant grass. It was a sight to make a man long for it, and Fai was no exception. He had no doubt Autumn was speaking the truth.

With difficulty he tore himself from the gate, and looked back at Autumn. “You want her happiness, too,” he said.

“She’s my sister,” Autumn said, and for the first time there was pity in her voice. “I love her.”

Fai said, softly, “Our parents love her too. They believed they were doing the best for her. You’re doing what you think is right, I know, but this has to stop.”

Autumn said nothing.

“You’re doing the same,” Fai said. “You’re forcing her into what you want for her. Not what she wants.”

Autumn’s eyes blazed as red as fireworks. “How dare you?”

She raised her right hand. A red sword leapt into it, and she was about to strike when Fai said, shaking, “Ask her. If you’re so sure you’re helping her, ask her.”

Autumn stopped her strike, but left the sword hovering at Fai’s throat; he could feel the point ready to pierce his skin, imagined himself falling, leaving Jun behind. “Ask her,” he whispered.

Autumn made a sweeping gesture with her hands; Jun appeared before the gate, bewildered. She looked pale, like the ghosts, but not yet pale enough to be dead. She was alive. She had to be. Surely Ming-Mei wouldn’t kill her own sister?

“Jun,” Fai said. He stood unmoving with Autumn’s sword at his throat.

She looked at him, at Autumn, taking in the whole of the scene with dark, shadowed eyes.

“I’ve come to take you home,” he said.

“He’ll make you marry a man you don’t want,” Autumn said.

Jun said nothing.

“They are ghosts,” Fai said. “In a ghost country. Nothing grows, nothing changes. In this world, you have a life with Zheng Yi ahead of you. The life you dreamt of.”

“You are free,” Autumn said.

Jun’s eyes met Fai’s and slid away, but not before he saw the tears in them. “I can’t please both of you,” she whispered.

“You wanted this wedding,” Fai said.

“And my sister?” Jun said. “Should I abandon her? She has no one left.”

Autumn looked at her, cocking her head.

“It’s a cold country,” Jun said. “Of dead people. Of cold people who can’t feel anything anymore. Like you,” she said to Autumn. Her face twisted, as if she’d break down. “You’re Immortal. You could feel things, but you don’t. You have no one. You love no one. You lived only for your revenge on Si-Jian, and now that you’ve had it, there’s nothing left to you.”

“I love you,” Autumn said. “Isn’t it enough?”

Jun did not speak for a while. She made an odd gesture with her hands. “Yes,” she said. “I am the only thing that warms your heart.” She wasn’t boasting; her voice was sad.

She looked at Fai.

“I told you that I wanted you to be happy,” Fai said. “I know how much you dreamt of that wedding.” You’re not Autumn, he thought. You don’t want your freedom at any price.

“Yes,” Jun said. Her eyes drifted to Autumn again. “But sometimes dreams aren’t worth enough. Don’t you see, Fai?”

He didn’t. But Autumn had sought to coerce Jun, and so had their parents. Even he had gone after her partly out of selfishness. He’d thought he knew what Jun wanted. That he knew what was best for her.

“No,” he said, at last. “But I will abide by your decision.” Uttering those words cost him more than he had believed it would.

Jun’s face was expressionless; there might have been tears on it, or perhaps it was just the reflections of the water on her skin. “I’ll stay,” she said, slowly.

Autumn looked from Fai to Jun, and then back at her own country. Her face was emotionless, but her eyes said otherwise. “You would do this for me?”

Jun did not answer. Fai didn’t either.

The sword at his throat quivered, stung him. He bit back a cry.

“Go,” Autumn said. The blade in her hand faded to nothing.

“Ming-Mei,” Jun said, extending her arms, but Autumn wasn’t looking at her anymore.

“Go away,” she said. Her voice might have been shaking, but it was hard to tell. “Have your wedding, be happy. Live a long, full life. And stay away from rivers. Stay away from me.”

Autumn dug her heels into her horse’s flank, and drove it onwards, towards the waiting gate. She passed into her country, followed by her stream of ghosts, and then the gate closed.

Jun had moved, shaking, to Fai. He was standing, staring at the place where Autumn had disappeared.

“She will be the loneliest of us all,” Jun said, slowly. “By her choice.” Her eyes closed, for a brief moment. “Was there anything more we could have done?”

“I don’t know,” Fai said. He raised a hand, fingered the drop of blood at his throat, thinking of Autumn, still gathering ghosts in her country long after both he and Jun were dust in their graves, still enduring her loneliness. He wished for an answer, but there didn’t seem to be one that felt right. “I don’t know. You chose to stay, and she wouldn’t allow you. She made a choice; you can’t come back on that. Come, let’s go home. Your bridegroom will be waiting for you, if you still wish to marry.”

Jun shivered. “Yes,” she said. “Let’s go home.”

They walked back to Fengjin together in silence. Behind them, the white light of the moon played on the rushing waters, a drowned, colourless memory of the sunlight in Autumn’s country.

END

Honorable Mention, Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror: Twenty-First Annual Collection , ed. Ellen Datlow, Kelly Link and Gavin Grant

Want more? Download a short fiction sampler (which includes this story) here.