Obsidian and Blood setting, 3: The Sacred Precinct

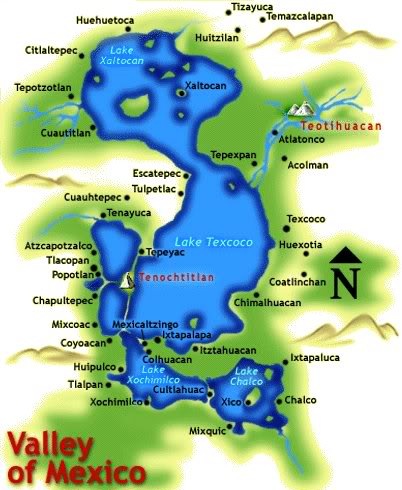

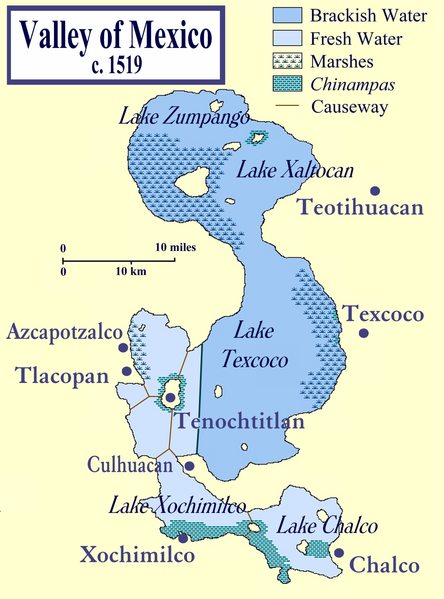

This is part 3 of a series of posts on the setting of my Aztec fantasy series Obsidian and Blood, as a leadup to the release of Book 1, Servant of the Underworld, published by Angry Robot/HarperCollins (more information here, including excerpts and a book trailer). You can find part 1 (the Valley of Mexico) here, part 2 (the city of Tenochtitlan) here, and part 4 (Acatl and death in Mexica religion) here.

Any questions or comments welcome!

3. The Sacred Precinct

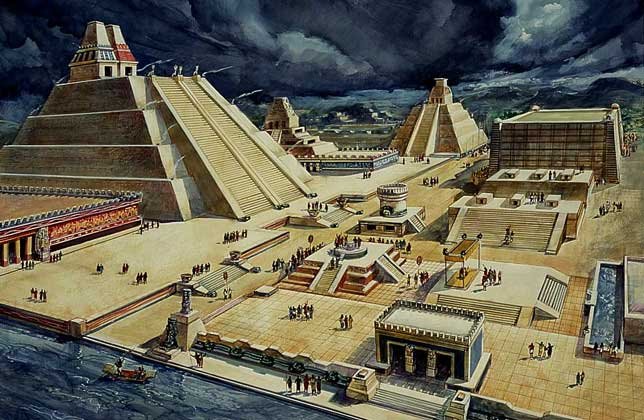

Just as the valley of Mexico was the heart of the Empire, so the Sacred Precinct was that of Tenochtitlan. Its function was simple: to serve as the religious and ceremonial centre for the city.

Within the Serpent Wall that delimitated its boundaries, the Sacred Precinct included the major temples of Mexica gods, areas for specific sacrifices, and the houses and schools for priests. Its size was staggering–500m to a side, probably the reason why the Spanish maps of Tenochtitlan give it such a prominent (and distorted) place.

Mexica religion is a complex field, not least because the only information we have about gods came through the Spanish friars, who tended to be biased on such a fundamental subject. There are dozens of Mexica gods, each with several aspects: Tezcatlipoca, the Smoking Mirror, the god of war and fate, is also Yaotl, the Enemy, and Telpochtli, the Male Youth, patron of the education of young warriors. The sum of those aspects are often referred to as “complexes”: though the gods have separate names and aspects, they take their root in the same basic concept.

To understand the Mexica relationship with their gods, it’s once again necessary to go back–this time to the beginning of the current age[1]. When the sun first rose in the sky, it remained motionless, transfixing the land with its deadly rays. The gods, seeing that the sun was hungry, sacrificed themselves and gave him their blood, so that creation might go on. Men are thus macehualli, “born through divine sacrifice”, and, because the (dead) gods can no longer feed the sun with blood, that most sacred of duties falls to mankind.

Sacrifice to the Mexica was not cruelty or mere bloodthirstiness–rather, it was a fundamental act, continuously keeping the end of the world at bay. It was a ritual, and even in the aspects that horrify us the most, the point wasn’t to cause pain for pain’s sake: the Mexica did not practise torture, and were horrified when the Spanish had such casual recourse to it. Rather, a sacrifice victim became a substitute/incarnation for the god, recreating the fundamental sacrifice the gods had made at the beginning of time–giving their blood for the sun and the continuation of the current age.

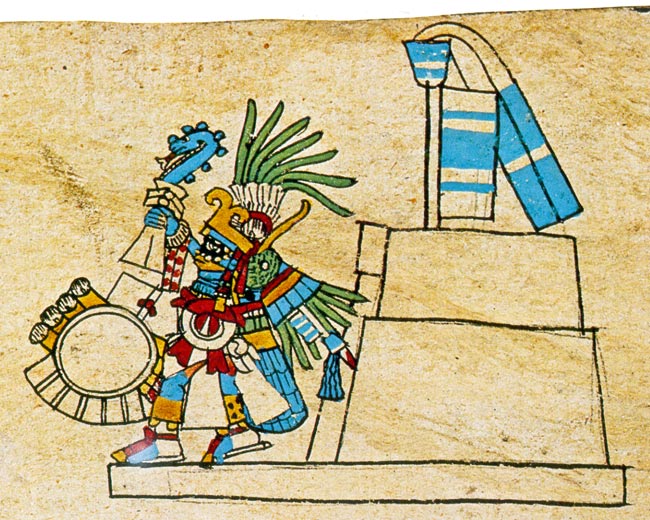

Of all the gods of the pantheon, the two most important ones had place of pride in the Sacred Precinct: the largest building there was the Great Temple (Templo Mayor), a twin pyramid dedicated to Tlaloc, the god of rain and storms, and to Huitzilpochtli, the tribal god of the Mexica. Tlaloc, characterised by his google-eyes and by the fangs protruding from his mouth, was an old divinity (traces of him are found as far back as Teotihuacan, a millenium before the Mexica). Huitzilpochtli, a youthful man with a blue-green hummingbird headdress and a black mask around his eyes, was a newer god, elevated to supreme rank and twinned with Tonatiuth, the Fifth Sun, the provider of light and upholder of the world’s order. He was a god of war to whom prisoners were sacrificed; celebrated during numerous festivals. Below are images of both, drawn from various Mexica codices.

Two other gods also had large temples: the first was Tezcatlipoca, the Smoking Mirror, god of war, fate and rulership. It was before Tezcatlipoca that a new Emperor would meditate and do penance before being crowned. Tezcatlipoca was a capricious god, as likely to curse as to help–another of his associations was with sorcerers, the dark ones who used potions and body-parts to poison men, rob houses and despoil innocent people.

The second, and the last one I’ll mention in this very short introduction, is Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Serpent. Under the name Ce Acatl Tolpitzin, he had been the ruler of the legendary Toltec city Tulla–his reign a golden age with no sicknesses, famines or human sacrifices. His temple in the Sacred Precinct honoured him as Ehecatl, the god of wind: it was a round tower without any asperities, so that it would not break the wind’s course as it sped through Tenochtitlan.

Among the other curiosities of the Sacred Precinct was the temalaccatl, or gladiator stone, where a captive warrior was given wooden weapons to fight against other, better-armed warriors until he finally succumbed; and the Jaguar and Eagle Houses, communal places for the elite warriors, those who had captured more than four prisoners on the battlefield. [2] My main character’s brother Neutemoc is a Jaguar Knight, and he would have looked much like the one depicted below: a full bodysuit made of a jaguar’s skin, the helmet worked out of the animal’s head so that the warrior’s own head protruded from between the teeth of the jaguar.

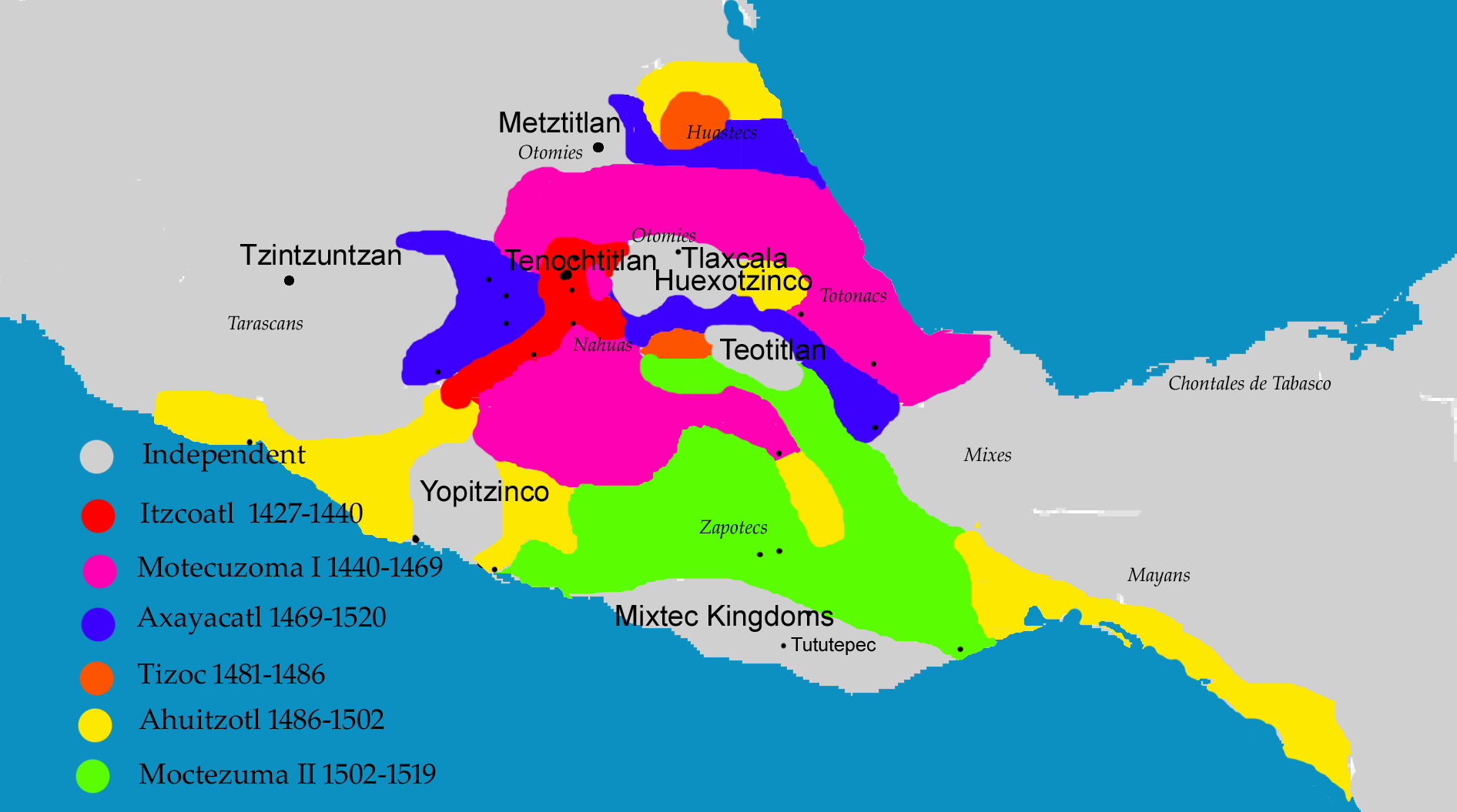

Though the emperor was the closest thing to a god on earth, standing for the authority of Tezcatlipoca and Huitzilpochtli, he did not live within the Sacred Precinct, but rather just outside it. We have evidence of several palaces built along the Serpent Wall, bordering the Precinct: that of Axayacatl (1469-1480), Ahuizotl (1486-1502) and Moctezuma II (1502-1519). It’s not clear whether the other emperors chose to inhabit a predecessor’s palace, or whether we haven’t yet found evidence of other constructions.

Those palaces were huge compounds, spread over a square kilometre or more: as well as a living space for the emperor and his family and the other members of the Triple Alliance, they also housed the courts of appeals, the workshops of imperial artists such as featherworkers, and goldsmiths, the treasury that held the tribute from the whole empire, and many other administrative functions of the empire. There were separate courts for civilians and the military, and the emperor acted as the supreme appeal. Those courts obviously play a large part in the book, which is focused on investigations and their consequences.

That’s all for today. Come back tomorrow for the final article, on my main character Acatl, and the Mexica approach to death (and the book launch, of course 🙂 )

[1]The current age was the fifth one in the cycle: previous ages had ended in worldwide disasters such as floods or rains of fire, and with humanity either completely wiped out or changed into animals. The current sun, Tonatiuh, is also referred to as the Fifth Sun. In the novel(s), I use the term “Fifth World” to refer to the mortal part of the universe, by analogy with the Fifth Sun.

[2]The orders of the Jaguar Knights and of the Eagle Knights tend to be listed as a single large body, with a single set of buildings. I have chosen to give them separate compounds, for plot-related reasons.