Article: The stories I wanted to read

I’m ten, and voraciously reading–bespectacled, and a head shorter than everyone in class, good at maths and utterly oblivious to the fact that I’m different from everyone else (only later will I work out that the string of people asking me “where do you come from” are comparing me to a class that’s 99.99% white and Catholic, and where the next most diverse person is the lone Ashkenazi Jewish kid, who probably isn’t having a great time either). I take to Science Fiction and Fantasy [1] like a fish to water: people fleeing this world for another; the wonders of space and faraway history where magic is real–where a farmboy can rise to become king; where ordinary people can stop evil in its track; and where science is a force for good, and the future has everyone equal without questions of creed and race.

There are a few… wrong notes, though. I cannot help but notice that Tolkien’s heroes are basically Europeans; and that the Easterlings–yellow-skinned or swarthy–seem to be mostly fighting on the side of evil. I cannot help but notice that most of the cool things in the future seem to be happening to men; and that, for all the talk about appearances not mattering, most women seem to need to be blonde, and young, and beautiful; the dark-haired, yellow-skinned ones mostly seem to be left by the wayside or to be antagonists.

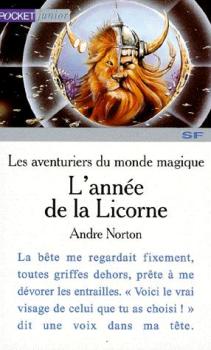

In the midst of this, Andre Norton’s Year of the Unicorn is a breath of fresh air. Gillan is dark-haired and more clever than pretty; and she waltzes through the book on (it seems to me) nothing more than sheer strength of will, and a stubborn refusal to be left behind, or to take anything at face value. When she does get left behind, she fights tooth and claw to find her husband; and make a place for herself in a world that doesn’t want her.

I love Gillan; and I reread the book over and over. It’s not, after all, so hard to see why.

There’s a lot of books in my reading that feature China, or some representation of the Far East–I read them all like I read invented worlds, because the China they depict is so out of touch with my family stories (I won’t say my family stories are all positive! Vietnam has… a complicated relationship with China)–surely they have to be about some kind of fictional China/Far East that doesn’t exist. They speak of martial arts and inscrutable, passive people awaiting to be saved; of some fount of mystical wisdom that awaits the traveller. I think fake!China must be some kind of faraway land invented by writers, because it cannot possibly be the real thing.

I’m in my twenties, and I still love maths, and work to make a living out of it. I discover the American Library in Paris, and discover Le Guin; and it’s like a revelation: SF doesn’t have to be about equations and maths. The SF that speaks to me is about people in the future, about their interactions with technology and with each other; but I’m less interested in whether the technology is feasible. I design feasible technology for a living; and books that strongly focus on this as an element remind me too much of my day job.

As I’m checking out all the Le Guin books ever written from the library, I read The Word for World is Forest. Many, many years later, someone tells me that it’s an allegory of the Vietnam War. I blink, because I know all about the Vietnam War; because it’s shaped my entire childhood; and this isn’t the image that I have. My Vietnam War involves pain and heartache and displacement, and massive family upheavals–not this odd (though good) story about colonists savagely exploiting an alien species, and the natives rising up against them. I realise, then, that there are always several sides to a story; and that not all stories are given the same precedence.

I start writing. I have a master’s degree in science, and general knowledge of physics and electronics; and yet I still do not feel confident that I can write science fiction. I have this image–propagated through books and discussions on forums–that true science fiction is rigorous scientific extrapolation (whether that science is mathematics or anthropology), and I feel I don’t have the credentials for any of this. It will take me many, many years to understand that this set of expectations is stifling and silencing me; and that I’m my own worst enemy, telling myself not to write because I’m not good enough. That I’m far from being the only one in this position or with this experience–that definitions of “proper SF” can end up being a cage for writers and readers alike, an excuse to dismiss everything that doesn’t seem to conform.

I still read books. Most have silent women, or women who use their looks as a weapon. There are no female friendships. There are no mothers, no families. People drink coffee and speak English, and most of them are blond and pale-skinned. When someone who does look or sound familiar appears; when someone seems like they’re going to respect their ancestors and value their families–they’re the aliens. They’re the funny guys with odd customs colonists meet, the ones they try to commerce with or understand or (in the worst cases) subjugate. They’re the invaders that have to be fought back for the sake of civilisation.

And I think “what civilisation?” I wonder how people like me fare, in the future. Or in the re-imagined past of fantasy. Probably not well.

I publish my first stories. I go to cons. I meet other people, offline and online, and start having my first long discussions about genre. I start thinking about what SFF really is. I meet other POCs, other women; learn about feminism; read a lot of essays. I learn that I am not alone; that others have had those same experiences; that others struggled or are struggling, trying to reconcile their love of SFF with that feeling that those universes have passed them by.

And then it hits me: if I want to have a place in those futures, in those reimagined pasts, I’m going to have to be like Gillan. I’m going to have to forge ahead, in the footsteps of those that came before. I will write my own stuff. My universes do not have to be white, or scientific, or sterile and lonely. And, if I don’t write my own experiences, my own cultures–then who is going to write them for me?

I wish I could say it goes without a hitch from there on. That I don’t have the odd conversation (“you write wonderful aliens!” in reference to my future diaspora Vietnamese people); the shouts from various corners telling me I don’t write proper SFF. The nagging doubt that perhaps–just perhaps–they’re right, that there’s no place for me at this table. It’s nonsense, of course. It should be. But thirty years of conditioning are hard to break through; and pushing through boundaries sometimes feel like pushing through tar.

That’s me and SFF, I guess? I feel kind of embarrassed sharing this, but I think it needs to be said–I’m not writing because of politics, or because I want to preach (well, sometimes I do want to write about specific themes that speak to me. But who doesn’t?). At heart, I’m writing my stories: the stories I wanted to read as a child, the adventures in space where I don’t have to feel excluded; the fantasies where you can be small and dark-haired and Asian and still be a hero. At heart, I’m sharing my side of the story, and the things that matter to me–war and exile and devastation, relationships between mother and child and extended families and how these evolve and change in the future. I love SFF. I want to see it thrive and grow and change; and include more and more people from all walks of life. And some of those changes will be uncomfortable. And some of those new stories by new writers won’t be for me or won’t speak to me, and that’s quite fine, because they will speak to someone else.

I hope that things will continue to change. I hope that the taste for this kind of stories grows; that there will be a wider appetite for them as people discover them. I want a future where it’s ok to write the kind of stories I wanted as a child; and where people read them and enjoy them and it becomes a new, significant chunk of the field (and it’s already happening, to some extent, for which I am very grateful). I want the field to reach outwards, step after step after step; until the table is large enough to include all of us on the margins, and we all learn to appreciate and love each other’s experiences and conceptions of the future–for, if SFF isn’t about openness of mind and change, then what is?

[1]It will be many years before I am aware of science fiction as a genre and consciously seek it out; but even before that it makes up the bulk of my reading.

0 comments

Paul Weimer

Thank you so much for sharing this, Aliette. If SF isn’t about change and growth, then no genre is. I don’t want an idealized past that never was. I want to go forward.

I can enjoy Vance and Anderson and Asimov…and look forward to reading Ken Liu, Ilana Myer, and, well, *you*.

aliette

Aw thank you for reading! I’m glad I’m making sense 🙂

>I want to go forward.

Me too! I just hope that we continue to grow. It’s important to acknowledge the past, but it shouldn’t become a prison.

Shana DuBois

Thank you for sharing this! I adore your stories and writing. I feel more at home in the warmth and feeling woven into your worlds than I do in the coldness of stringent SF from days past. I can relate to many of the sentiments you shared. Even with our backgrounds being 180 degrees different, your words and feelings resonate with me on a deeper level as I always felt alone in my world. Thank you again for sharing and I look forward to reading all your stories!

aliette

Shana–thank you very much! I’m glad it’s speaking to you as well. I hope that one day we get to the point where no one has those experiences anymore (yeah, I’m choosing to be optimistic).

Tony Lane

Beautiful blog post. I read it twice.

aliette

Thank you Tony! The response to it has been overwhelming, and the support much needed.

Howard Tayler

That was beautiful. Thank you for sharing it, and doing so in such a vivid and wonderful way.

aliette

@Howard: Aw thank you so much! I’m very glad it spoke to you.

Wendy S. Delmater

As I’ve reached out over the years for diversity of thought and experience to share with our readers, I’ve always thought of you as a treasure. I’m pleased that we at A&A were part of your early career and that you’re now one of the stars in the SF&F firmament.

And I can relate. Despite having parents that really meant it when they said I could be anything I wanted to be (mother was a chemist, father a teacher who taught me everything from how to repair my own car to how to deal with hierarchical males) – SF looked like a guy game to me. When I discovered that Andre Norton was a female, I realized I could be a part of it, too.

Micah

What a read. And I can definitely relate. Thanks for writing this.

RSA Garcia

So much of this parallels my own path. I’m relating all over the place.You will inspire many by sharing these insights. It’s always good to know you’re not alone.

Sherry

Good post. Well written. You should read Lois McMaster Bujold if have not already done so. You will find a lot of adventure, amid great character studies and some of the greatest quotes ever. A great character like all of. Bujolds transcends their physical discription and background with bravery, love, determination, and personal growth. You will never find a better character study than the growth of miles Vorkisigan from 17 to 32. Read and enjoy. I think you will find it helpful. I especially recommend memory. I have never encounter a better book dealing with loss and change. The character looses everything he thought he needed and has to start over again. Read from the beginning or you won’t understand the depth of the loss .

Katherine

I grew up in the 50’s. I loved Sf&f as a child but I made my brother check science fiction out of the library for me because I thought it was only for boys. I didn’t realize Andre Norton was a woman until I was in my 20’s.

I got to a point where I was mostly reading books by women because I just couldn’t stand reading most men’s work. They just didn’t relate to me and my experience.

I love the new voices I’m reading now. I love the diversity. It feels like the world I live in which is not just populated by white men.

Aliette, I’ll be looking for your books.

aliette

Wendy: aw thank you! Very proud to be an A&A alumnus. And lots of people came to genre via Andre Norton! Such a shame a lot of her stuff is out of print now.

Micah: thank you! I’m glad it spoke to you.

RSA Garcia: It is always good to know that’s not alone. I know I derived lots of strength from the support of others.

Sherry: I love the Vorkosigan books! (my favourite is “A Civil Campaign”, actually, because it’s such fun). “Memory” is good too, in a heartbreaking way.

Katherine: I know what you mean! It was always a revelation to find an author I could relate to (it’s not always women, but women do start with an advantage because they know what other women go through). And I’m glad for diversity too; there’s lots of new voices and lots of very different stories. I hope it’s only the start (I’m pushing for more work outside the Western Anglophone hegemony. Singapore, Philippines, India…). And hope you enjoy my books 🙂

Val

When I read I want to go somewhere else. Some place I am unfamiliar with. Reading is a way to get to places you will most likely never go to, or only visit briefly. It is a way to go to places that are an extrapolation of what might be, where different ideas and ways of living can be explored. Last week I was traveling around Martin’s thousand worlds, right now I’m in 19th century Mali, next week it might be Liu’s Dara or Walton’s Just City, or some place else entirely.

This desire to find these other places is one of the main reasons why I read SF&F. It offers untold possibilities to travel, to create and to experiment. To limit it to an idealized version of one culture, one language ect, makes no sense to me. It is buying a book and then read only one chapter. So bring on Prosper station, aliens landing in Lagos of Lui Cixin’s future China. I’m ready for them.

aliette

Aw thank you! I agree. That’s also why I read SFF. And the Single Story (as Chimimanda Adichie says) is such a pernicious, dangerous, erasing trope.

Nim

Following your works since the jaguar priest. Loved it and look forward to more. 🙂

Georges

You know, Aliette, event if I am a man, white, nonchristian, I found, perhaps not froùm the beginning of my readings, but for a long time, that SF includes a lot of open stories, with not male, not occidental, even really not human (which means not a mask for some human existing culture) characters and heroes. When you tell us how you still see there would be some kind of “proper SF” to whioch you wouldn’t belong, I think that you describe a Sad Puppies’ world, and not what SF has been since it began, an open field where all kinds of change and of cultures are welcome, where, from the beginning of this branch of fiction women and “feminine” subjects (if sexual separation of ideas would be possible) have invaded the whole subject. You remind us of Andre Norton and Ursula Kroeber Le Guin, but what of Francis Stevens (Gertrude Bennett Barrows), Margaret Saiont-Clair-Idriss Seabright, Catherine Lucile Moore, Leigh Brackett, Marion Zimmer Bradley, only to cite some of the oldest women SF writers (not forgetting Mary Shelley if one wants to cite precursors). And, about themes and respect for other cultures, how many “male” writers have, since the pulp magazines, created strong or important female, or not “WASP”, characters? You, Len Liu, Linda Nagata and others, do not have to conquer an hostile land, to make your place: it has been here since the beginning of SF. And SF wouldn’t even exist if it was the “proper SF” that you dread. Welcome home.

Joanne Hall

Brilliant post, Aliette.

aliette

Joanne, Nim: thank you!

Georges: there’s definitely an issue there of canon or what is widely available–it’s not a secret that, to take just an example, SF by women writers goes more frequently out of print and is harder to find. My experience of SF was dictated, largely, by what I could find in libraries and bookshops. I don’t think of SF as a hostile land; however, I do feel the need to push for greater diversity in the field (to take just a recent example: the Hugo Awards, widely recognised as one of the most prestigious ones in the field, overwhelmingly go to US authors–to brutally simplify a not-so-simple issue, because they’re for English language works, and few works get translated into English http://aidanrwalsh.com/2015/04/21/371/ )

Diane Severson Mori

Thank you, Aliette, for this heartfelt, deeply personal post. You say it like it is, and it’s clear SFF has often disappointed and yet you are, at the same time very optimistic, which is refreshing. I’m very much looking forward to many more of the stories you’d also like to read.

aliette

Thanks Diane 🙂

Georges

Aliette, I understand your feeling, but such a feeling is exactly what aggravates the situation. And a feeling which should be fought and eliminated after a sufficient time of reading, writing and meeting SF fans, and of defending that you write SF, not fantasy.

Sorry. Comments are closed on this entry.