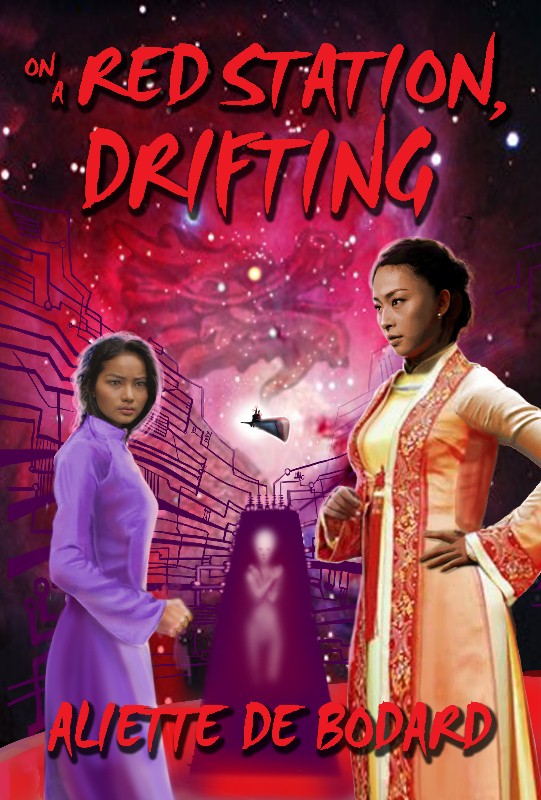

Author’s notes: On a Red Station, Drifting

So, it’s occurred to me I didn’t actually provide this for my latest release–accordingly, there you go, author’s notes for On a Red Station, Drifting.

So, it’s occurred to me I didn’t actually provide this for my latest release–accordingly, there you go, author’s notes for On a Red Station, Drifting.

I started writing On a Red Station, Drifting after one too many readings of the Chinese classic Dream of Red Mansions, and musing on old literature.

It’s no secret that “classical literature”, at least the brand taught in French schools, is overwhelmingly male and concerned with “male” affairs: wars, violence, fatherhood, father/son relationships… I found the same preoccupation prevalent in SFF, to a point where it became unsettling–it’s a subject covered by Ursula Le Guin in her Language of the Night and by Joanna Russ in many of her writings. One of the things that drove this home for me was seeing the statistics compiled by Martin Lewis for the Clarke Award (among the highlights: around 90% of the books had at least a male protagonist, a good quarter featured no women main characters at all, and a good 81% of the books had the protagonist kill someone, while only under half the protagonists were in a stable happy relationship).

Dream of Red Mansions, meanwhile, a novel that was written in the 19th Century, has 12 central female protagonists (and an effeminate, somewhat ineffective male protagonist who often wishes he was a girl), a slew of relationships from husband-wife to various degrees of family closeness. Its Twelve Beauties of Jinling are very different women, from the fierce and domineering Wang Xifeng to sickly and grudge-prone Lin Daiyu. It is explicitly written as a homage to those women; and its focus is resolutely domestic. It concerns itself with the affairs of two related households (the Rongguo and the Ningguo houses of the Jia family), their day-to-day intrigues and relationships, while the great events of the period are relegated to the background (the very strong political upheavals of the time period are only alluded to when they impinge on the family’s everyday life). I thought it was an awesome way to write a book, and I decided I wanted to try my hand at a domestic plot.

Only, it had to be a space domestic plot, obviously–the closest future equivalent I could come up with for a great household was a space station. For convenience’s sake (and for pleasing fans 🙂 ), I opted to set this in the larger-scale Xuya universe, which had human-borne AIs, the Minds, run spaceships. It was but a small stretch to imagine those same Minds used to stabilise space stations. And so was born Prosper Station, an isolated corner of a future Đại Việt home to the Lê family since generations (its name, Prosper, is a shorthand for Prosperity, as I imagined a loose alliance of space stations named after the Three Blessings of Longevity, Prosperity and Felicity).

I imagined that a great war had emptied the station of its most able people, leaving only civilians unused to governing (the great war itself has more than a few echoes of the opening salvoes of the fratricide Trịnh-Nguyễn war). In this universe, there is no gender discrimination, but a discrimination on achievements: the most accomplished partner of a marriage is the greater partner (and has the right to marry several times); the other one is relegated to the more domestic tasks of the household. In the case of an understaffed space station, though, “domestic” could mean lots of things, as my main character Quyen discovers…

I chose to make women the focus of this novella, and to split the point-of-view between two very different women: Linh is an official used to power; Quyen has been thrust into managing an entire space station and struggles against her own sense of her inferiority. The structure I arrived at is in three books, each centred around a visitor to the space station; each visitor bringing with them a particular upheaval to the already precariously balanced situation.

Writing the novella was like pulling teeth. I kept slipping up, and doubting myself. My original plot, which revolved around children, got tossed out the window as too clichéd and too male-centred; my scenes got swallowed up one after the other as I struggled with rewrites. My crit group, faced with the first draft, balked at the complexity of the society and the number of secondary characters. I edited a lot of things out: you can catch a glimpse of the removed characters in the first scene where Quyen runs through the space station, and at the banquet scene near the end of book 2. Huu Hieu and Bao were originally two spouses of the same absent official, but that also got cut because it was too complex to explain in the limited space I had.

One of the biggest hurdles I faced was ending the story: my original ending was an evacuation of the space station as the war finally engulfed that corner of space. I struggled for a long time to write it, until I realised I was letting violence-centred narrative get the better of me again: the main reason that ending wasn’t working was that there was no way my heroines were going to transform into gun-swinging, mob-organising badasses at the drop of a hat! I therefore switched ending to something far more restrained and more appropriate for the tone of the novella.

I fudged a bit in a few places (and quite probably got things wrong–I didn’t know as much Vietnamese back then as I do now). Notably, some people are referred to by their first names, and others (most notably Huu Hieu) by their first and their middle name. I did this because most English-speaking people already have difficulties telling Vietnamese characters apart, and I didn’t want to make matters more complicated for them by having mostly one-syllable names. Many women also have very simple names, whereas it’s more likely they’d have poetic names based on literary allusions (that, however, would have required a level of language and knowledge of Vietnamese poetry and literature I just don’t have at the moment)

And, of course, there is food. I am very proud that the centrepiece of Book 2 is a banquet (complete with poetry recitation!), and that the planning and execution of it is done with quite as much care as other people plan and execute ambushes. And where else would you find an entire chase scene in a fish sauce brewing centre? I researched this bit through watching videos of the fish sauce factories at Phú Quốc, aka the best research I’ve ever done; and also sat down and read lots of accounts of banquets in Imperial China and Imperial Vietnam (that was tough research. It has a natural tendency to make me very hungry).

Meanwhile, if you’re curious and want to read Dream of Red Mansions, the translations I’ve read are David Hawkes’ The Story of the Stone (somewhat plain and no-nonsense, but has the advantage of copious notes), and Gladys Yang’s and Yang Xianyi’s A Dream of Red Mansions, which doesn’t attempt to render everything into easy Western equivalents, but as a result can be a bit hard to read if you’re not familiar with Chinese society (there’s also a pretty cheap Kindle version here). And there’s also a great “graphical novel” version, which presents the novel through the brush of Sun Wen: A Dream of Red Mansions: As portrayed through the brush of Sun Wen.

(of course, you can also order the novella itself–see here 🙂 )

ETA: I’ve seen a bunch of people wondering over the Internet about the cultural basis for the novella. The Đại Việt Empire is broadly based on Ancient Vietnam, brought forward into the future. In particular, since French influence was much less present in the alternate continuity than in real life, a lot of the formalities are closer to the customs of a modern-day quasi-Ming-dynasty Chinese Empire, though I also went looking for inspiration in the customs of the Nguyễn court. I sort of cheated by keeping the language and food broadly congruent with Vietnam today: I thought it was going to be easier on the knowledgeable reader to have recognisable language structures and recognisable dishes (and also a lot easier on me since I didn’t have to play the fun but time-consuming game of “how would the cuisine have turned out if the French hadn’t arrived?”)

0 comments

Erin

Another recent reimagination (much too short to call an adaptation in any real sense) is Pauline Chen’s The Red Chamber — http://www.randomhouse.com/book/213551/the-red-chamber-by-pauline-a-chen

I’d be interested in seeing your thoughts on how it compares to an actual translation.

Meanwhile, I’m off to add the novella to my TBR pile!

aliette

Hi Erin,

Thank you for the recommendation–will check it out!

Laura Christensen

I’m so excited to read this! And thanks for the links on the original, I’ve been meaning to find a good translation to read. Your notes also remind me a lot of my current struggles writing my Manchu-history based novella, so–though it probably doesn’t help you, it really helps me. So, thanks!

aliette

Aw, thank you, Laura–glad I could be of help!

Carmelo

Happy to say all preorders will finish shipping today!!!!!

I am so happy–and exhausted in a good way–at the amount of response for this book. Thanks to everyone who preordered.

Bonnie R. Schutzman

Erin Hartshorn pointed me here. Your novella sounds wonderful. My husband enjoys history so I’m going to get the translation of A Dream of Red Mansions as well.

And I think the part about violence-driven plots might explain one of my stories that keeps flying apart in so many directions. It’s a violent world and the women I’m writing about can’t avoid that. One of them is a violent person; women aren’t immune. But that doesn’t mean I have to let the violence define them or the plot. Thank you for discussing this so honestly and clearly.

aliette

@Carmelo: awesome, glad to know it (and go get some rest 🙂 ) Thank you!

@Bonnie: aw, thank you! I recommend A Dream of Red Mansions, it’s definitely a great (though time consuming) read. And I am very glad I’m not the only one having those problems with violence and violent plots–good luck with your story!

Sorry. Comments are closed on this entry.